Eye For Film >> Movies >> Devil's Knot (2013) Film Review

Devil's Knot

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

On May the 5th, 1993, three young boys went to play in the hills near their homes in West Memphis, Arkansas. They were never seen alive again.

The following year, three teenage boys stood trial for the murders. They were Damien Echols (here played by James Hamrick), Jason Baldwin (Seth Meriwether) and Jessie Misskelley (Kristopher Higgins). They were accused of killing the boys as part of a Satanic ritual, in a case that hinged on their fondness for heavy metal music and preference for wearing black.

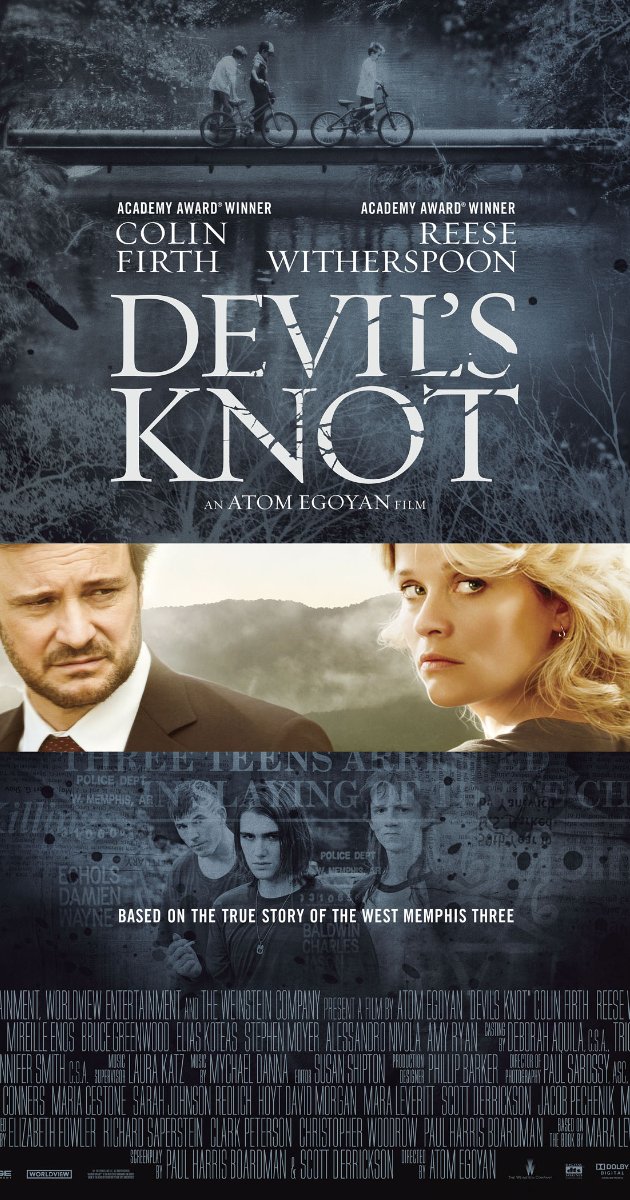

These are the facts in a case that has already inspired several films, including the documentaries Paradise Lost and Paradise lost 2: Revelations and the recent West Of Memphis, co-produced by Echols himself. This latest entry is an adaptation of Mara Leveritt's 2002 book, and approaches the story through drama, rearranging some minor details to help the narrative flow but sticking closely to the known facts in its depiction of the main events. It's aided by a highly capable cast, including Reese Witherspoon playing against type as the tormented mother of one of the murdered boys, and Colin Firth as the private investigator who stepped in to help the defence after coming to the conclusion that something was badly wrong with the handling of the case.

Like the book, this film is slanted toward the defence - there's little mention made of Echols' troubled psychiatric history, for instance - but even with a heavy bias in the other direction, it would be difficult to miss the gaping holes in the prosecution case. From the teens being asked if they believed in God to the elaborate stories told about them in court that were later acknowledged as fantasy, the failure of the police to follow up on other leads and the loss of material evidence - never mind the confession given by two other teens in Los Angeles, which might have been obtained using similarly suspicious interrogative methods - there's a great deal to suggest reasonable doubt. Moral panic is a powerful force, however, and it's worth remembering that the UK has seen similar cases in the intervening years - it's not just an artefact of time and place. The vital element in Atom Egoyan's slow burning, contemplative film is its success at capturing that. Egoyan helps us to understand this fervour, to observe it taking root in reasonable, relatable people and twisting their perspective. By way of counterbalance, however, we see Witherspoon's character gradually losing faith in the process, which gives emotional weight to an important point - that convicting the wrong people would leave a murderer at large and provide no real justice for the murdered boys at all.

Courtroom drama is always a challenge for a director, even when it's balanced, as here, with ongoing investigations and occasional flashbacks. Egoyan draws on the small town atmosphere and the sense of a traumatised community to deliver something reminiscent of The White Ribbon or Twin Peaks, an involving mystery which, alongside its immediate concerns, asks questions about human nature and the inherent mystery of mortality. The fact that, even today, there has been no uncontested resolution to the case gives this something of the power of Zodiac or the purely fictional Picnic At Hanging Rock - it has an obsessive quality that will make detectives out of viewers, sending them on the hunt for clues like many before them. It also touches on the ancient theme of sacrifice. There is a sense that condemning somebody for the crime is what is needed to provide closure, to heal wounds. When the need is so great, it almost ceases to matter who that condemned person is.

In her book, Leveritt compared the trial to the witch trials at Salem (where Echols now lives), and that allusion is brought up in the film, reminding us how closely literature and film are intertwined. The Salem trials were hardly the only events of their kind, but they're ones we remember because of the contemporary accounts, Miller's play and its various film adaptations. It was in part literary works about the occult, checked out from the local library, that built the case against the West Memphis teenagers. Now this film will take its place in the canon, this trial take on that fictional function and, in time, that mythical quality, until it is eventually raised in another real life case. Perhaps that's less frightening that the incomprehensible void left when a child dies. Whatever is the case, Egoyan's contribution is a powerful one and - perhaps most importantly - a human one.

Reviewed on: 12 Apr 2014